Why the Same Stores Are in Every City

Large businesses have been dominating for decades, while small businesses are no longer as common

Hey, everyone! My name is Jordan, and I have a Ph.D. in Economics from the University of Pennsylvania. I want to ask important questions and answer them meaningfully using the hard work economists have put into their research.

My goal is to have 500 subscribers by the end of the year. I enjoy teaching others about economics, so I put a lot of effort into condensing research and making graphs to make these posts fun (hopefully) and understandable. If you learn anything interesting from this, please like, share, and/or subscribe! Thank you to all my current subscribers for your constant support.

Throughout my life, I have often heard about the importance of supporting small businesses. From the early 2000’s, when Blockbuster, Kmart, and Toys R Us were booming, until now, when Dollar Generals are aggressively taking over the entire rural U.S. and Walmarts are universal. Where did this narrative of supporting small businesses come from? And why might we be seeing the same exact chain restaurants and stores when we take an exit on the interstate, visit a small town, or maybe even visit a big city?

Since 1990, many counties and local areas have seen a decline in physical business locations like shops, restaurants, manufacturing plants, offices — or what economists call establishments. You can think of establishments as buildings for, say, an Old Navy or a Chick-fil-A, and Old Navy and Chick-fil-A themselves are businesses. But the total number of “establishments” doesn’t tell the full story. We also need to consider how each county’s population has changed. If more people move into a county yet the number of establishments stays the same, then there are fewer establishments per person. Since establishment counts naturally rise with population, looking at establishments per person gives us a clearer view. The map below shows how we now compare to the year 2000:

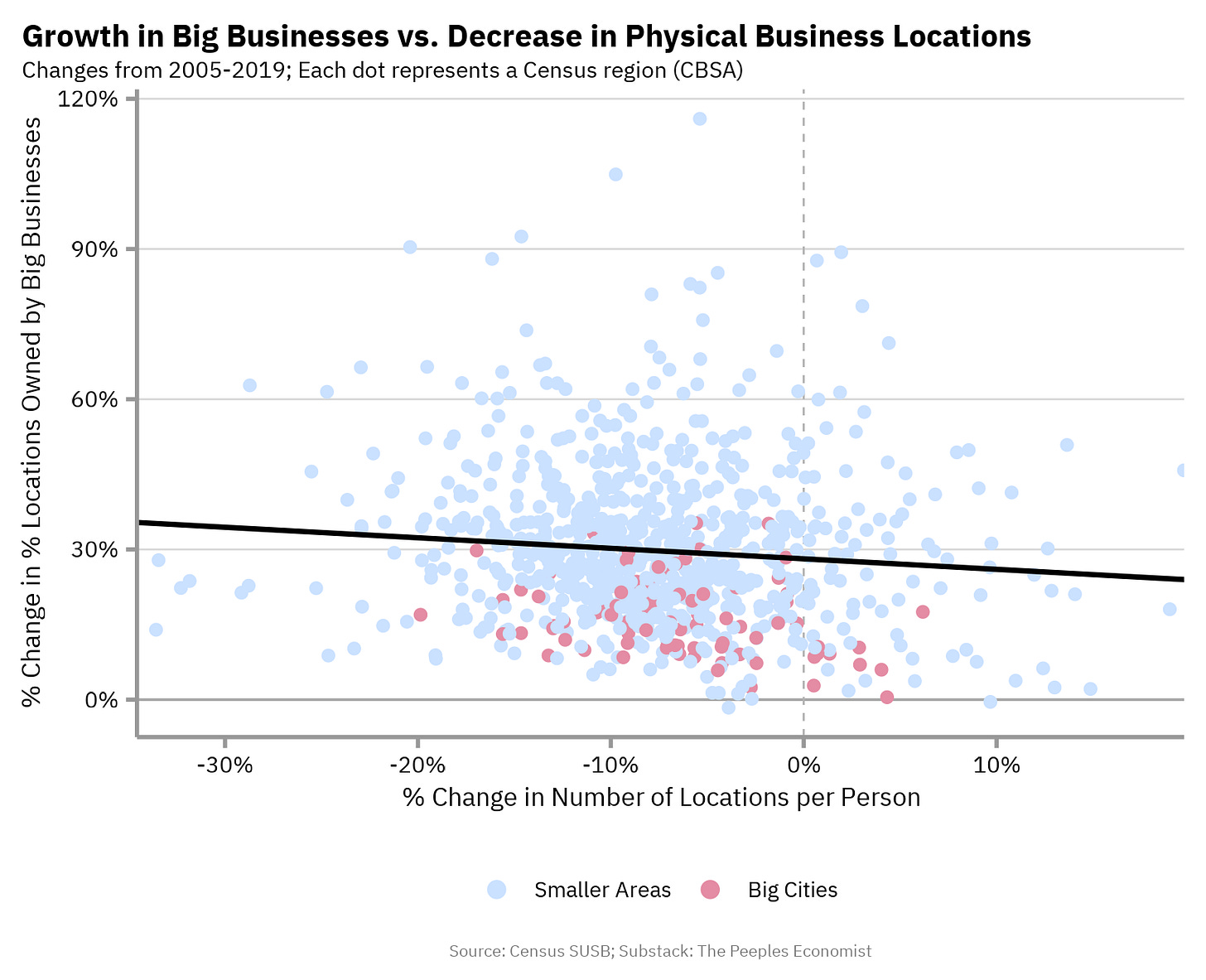

Many counties now have fewer establishments per person, though some have seen the opposite trend. This alone doesn’t tell us who owns these businesses or how competitive each area is — that part comes later. Still, there are a few possible reasons for the overall decline in small businesses. Larger businesses may be opening bigger establishments that serve more people. Businesses themselves may have become more efficient and are able to serve more people, especially large businesses. And as online shopping has grown, physical stores have become less essential in the retail space compared to warehouses and distribution centers. The graph below compares how the share of large businesses (those with 500 or more employees) and the number of establishments per person have changed across metropolitan areas.

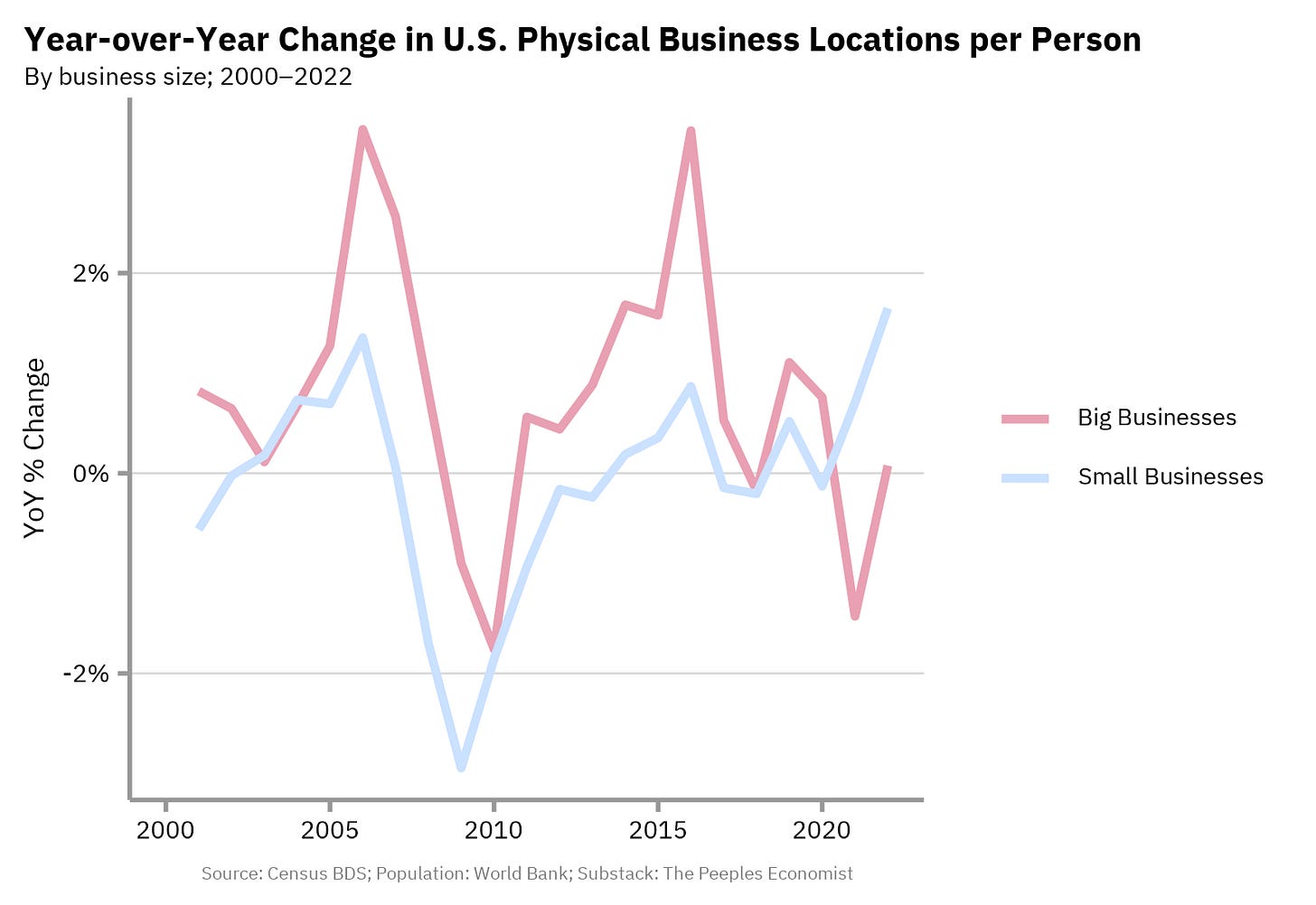

Cities that lost establishments (per person living there) often saw a rise in large businesses owning the ones that remained. At first glance, that might seem like proof that competition has vanished; but that’s not necessarily the case. Small establishments have struggled to survive over time, as shown in the chart below, yet establishments may still be almost perfectly competing within their markets, even if fewer of them are left standing.

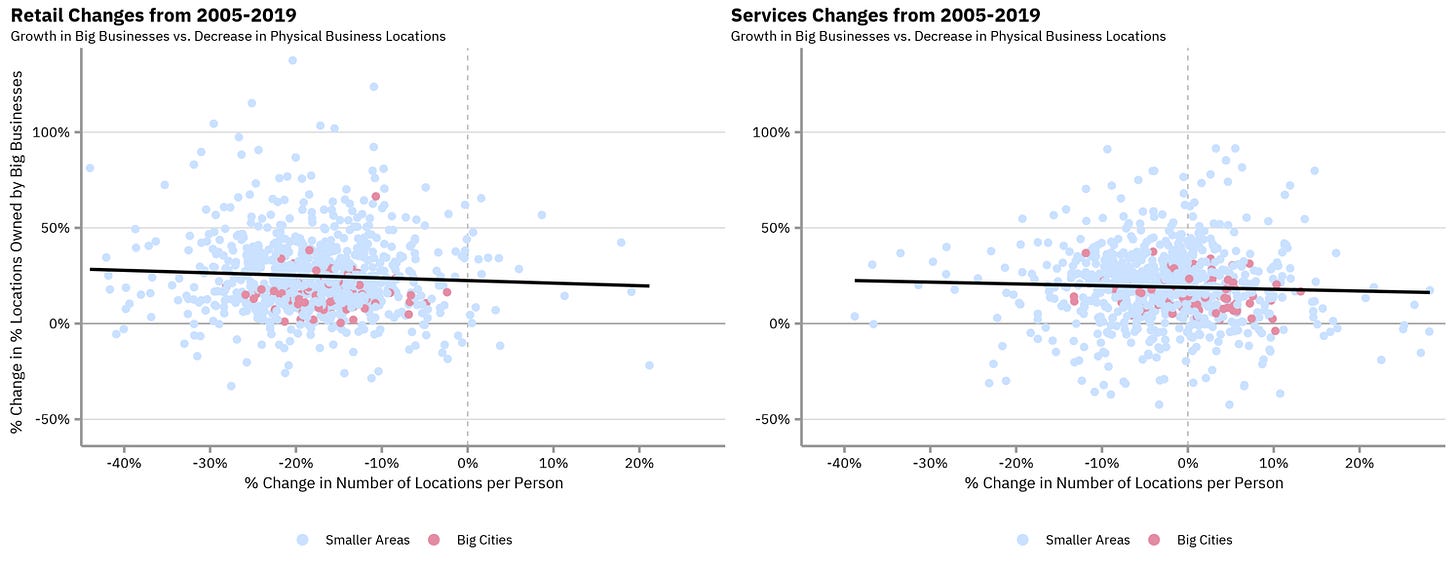

The “online shopping” argument would only be relevant for retail stores like Kohl’s or Nike, but not so much for restaurants or hair salons. While online shopping may have destroyed some of the physical retail stores, the pattern of decreasing establishments with increasing ownership by big businesses still exists for both retail and services, but retail has had a much stronger decrease in number of establishments. This is evidence that online shopping did have a strong influence on all retail establishments.

Now, imagine a small town with five stores. One is owned by Walmart, and the other four are small boutiques and convenience shops. Because the Walmart store offers lower prices and a wider selection, it captures most of the area’s revenue. Over time, three of the smaller stores close due to falling profits. Then a Target store enters the market and opens nearby, drawing some of Walmart’s customers. The town now has three stores instead of five, but sales are more evenly shared between the Walmart store and the Target store rather than the vast majority going to Walmart.

This idea comes from a recent economics paper. Nationally, economists have documented a rise in business concentration, meaning that a larger percentage of total sales is flowing to a smaller group of firms. In retail, for instance, more of the industry’s sales now go to giants like Walmart and Target. But the paper also finds something surprising: while business concentration has grown nationally, it has actually declined within local areas such as ZIP codes and counties. How can both be true? It mirrors the earlier example: Walmart and Target may control more of total U.S. revenue, yet they increasingly compete with each other in the same local markets.

But this is actually a debated fact based on semantics of the calculation being used; another paper finds increasing local business concentration when considering the sales an establishment has in an area but decreasing local business concentration when looking at how many employees an establishment has in an area. If that’s true, then maybe our example looks more like an area where smaller stores took up much more of the economic activity in an area, but they were then pushed out by Walmart and Target.

Either way, the rise in national business concentration is uncontested; big businesses have grown by physically expanding across the U.S.

Why are sales going to fewer businesses in the U.S.?

The rise in “business concentration” has become a major focus of economic research. Over the past few decades, the percentage of startups out of all businesses has declined while large businesses have continued to expand. This isn’t exactly the same as growing concentration (it’s a close relative called “business dynamism”), but it is a sign of growing business concentration. Fewer startups mean fewer new small establishments, which can lead to an older, more entrenched set of firms and greater concentration at the national level. Economists have offered several explanations for why this trend may be happening:

Decreasing labor force:

Since the 1980s, the total amount of people who are working or looking for work (i.e. in the labor force) has grown much more slowly. Two main forces are behind this shift. First, the population is aging as Baby Boomers retire. Second, the proportion of men entering the labor force has been decreasing since 1950, and the proportion of women entering the labor force stopped growing in 2000. An older population means fewer potential entrepreneurs to start businesses and establishments along with faster growth in wages, since the supply of workers isn’t rising as quickly. One study, using a macroeconomic model, finds that this slowdown in labor force growth explains roughly half of the decline in startup formation. Another paper reaches a similar conclusion.

The growing power of logistics and information technology:

In the 1970’s, the barcodes we see on items at stores today became popularized. Around the same time, shipping containers revolutionized how goods were transported. Since then, logistics have advanced dramatically, making it faster and cheaper to move products to stores. The rise of the internet and data warehouses added another layer: information technology, or the use of computers to analyze and manage data. Together, these innovations allowed businesses to better track inventory and optimize what they sold. One study found that barcodes and scanners alone boosted grocery-store worker productivity by about 4.5 percent, though they came with high upfront costs; this included everything from coding products into the system to redesigning packaging.

How does this connect to large businesses capturing more of the market? Implementing information technology (like computer systems devoted to tracking customer data) is really expensive and often too costly for small businesses to justify. Larger businesses, on the other hand, can absorb those costs and benefit from the scale that technology enables. They also have more customers, which means more data to analyze and use to refine their products and services. One study finds a positive, causal link between IT intensity and business size. Another paper argues that rising business concentration partly reflects growing gaps in “knowledge” between large and small businesses, and this divide widens as big businesses collect and leverage far more customer data.

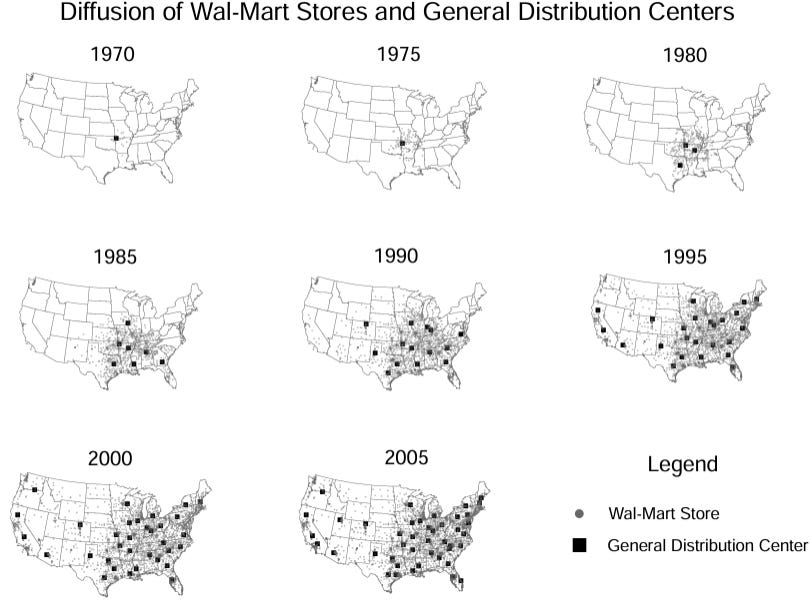

In short, information technology boosts sales and helps firms expand more efficiently, often through opening new branches across multiple counties. This helps explain why large businesses dominate so many local markets. Companies like Walmart combine logistics and data to guide their growth, strategically building stores near distribution centers to minimize transportation costs. These efficiencies made expansion cheaper, reinforcing the advantages that allowed big businesses to spread even further.

Mergers and acquisitions

A merger happens when two companies combine to form a new, single entity, while an acquisition happens when one company absorbs another. In recent years, acquisitions have become increasingly common, especially among public companies, which are firms that sell shares of stock to the public. This trend fits neatly into the broader story of growing business concentration and the expanding influence of large corporations.

One study finds that the rise in acquisitions explains much of the decline in the number of publicly traded companies. In other words, part of the increase in U.S. business concentration may come from large companies acquiring other companies. Another paper shows that smaller businesses are going public less often — not necessarily because of new government regulations, but perhaps because of the absence of policies and lack of enforcement allowing them to do so. As concentration grows and large corporations enjoy higher profit margins, the incentives for smaller companies to become public have weakened.

What does this mean for competition?

Large businesses are clearly expanding and capturing a greater proportion of sales within each industry (i.e. Walmart is taking up more retail sales today than it used to). But that doesn’t automatically mean competition has weakened. The key question is whether these companies are pricing their goods and services close to the costs it took to make them, earning significantly higher profits as a result. In other words, are bigger businesses simply more efficient, or are they using their market power to charge customers more?

These questions get at the idea of market power, which isn’t the same as simply having more sales. Market power refers to a business’ control and ability to set prices above the cost of producing its goods or services. When market power rises, competition weakens and consumers pay higher prices than they otherwise would. Whether businesses expanding across regions increases this market power is still debated. One study finds that it’s not the number of customers that drives a company’s pricing power, but how much each customer spends. The authors suggest that policies aimed solely at limiting business size may be misled.

A large body of research shows that these price markups (the gap between prices and production costs) have risen steadily over the past few decades, suggesting that “market power” has increased. Even though technologies like information systems have lowered costs and big retailers keep prices low, their profit margins have grown. One study finds that the difference between prices and costs is far larger today than it was in 1980, and corporate profits have climbed accordingly. Viewed this way, the efficiency we usually have with perfect competition has weakened, though not entirely because businesses have expanded nationwide. There is also some evidence that mergers and acquisitions increase price markups.

Conclusion

What does this mean for us? Well, one line of economic thought argues that having access to a bunch of different goods and services makes us “happier” or improves overall well-being. There is some limited evidence that when a business merges or acquires another business, it increases the variety of what it makes. But at the same time, fewer small businesses entering the market means fewer new ideas, less innovation, and a weaker match between talent and opportunity, all of which can slow economic growth. Policymakers could address some of these inefficiencies through measures such as providing R&D grants for smaller businesses or restrictions on non-compete agreements.

In reality, these policies probably wouldn’t be beneficial to small mom-and-pop stores that aren’t focused on expansion. From this perspective, larger businesses may simply be more efficient and create greater overall economic value. However, while larger businesses may be able to offer more products and services in a city than local mom-and-pop stores, many cities begin to look and feel the same when these businesses expand, which may leave us feeling like there’s not much to choose from when we visit new places. Growth may look like standardized buildings and familiar logos. And isn’t it telling that every example I gave in this article was in reference to a big business we all recognize?

A very simple TL;DR: Big businesses have been expanding across cities for decades. We have seen physical business buildings going away, while the ones remaining are mostly owned by big businesses. This has been caused by a decreasing labor force, advancements in IT and logistics, and an increase in mergers and acquisitions. This is not to say cities are becoming less competitive, but they are now beginning to look more and more the same. This can be good for ease of access in buying things but bad for economic productivity.

Really good article.

Fomalisation of an economy is a given eventually considering to efficiency merit but US is particular has seen hyper formalisation in most of the industies loosing the essence a mom and pop store or a family owned bar had back in the 80's and 90's

Sad.

"Still, there are a few possible reasons for the overall decline."

Jumping ahead, I know what you mean, but at this point, you have not defined the "decline"